What is the Hispanic Chant?

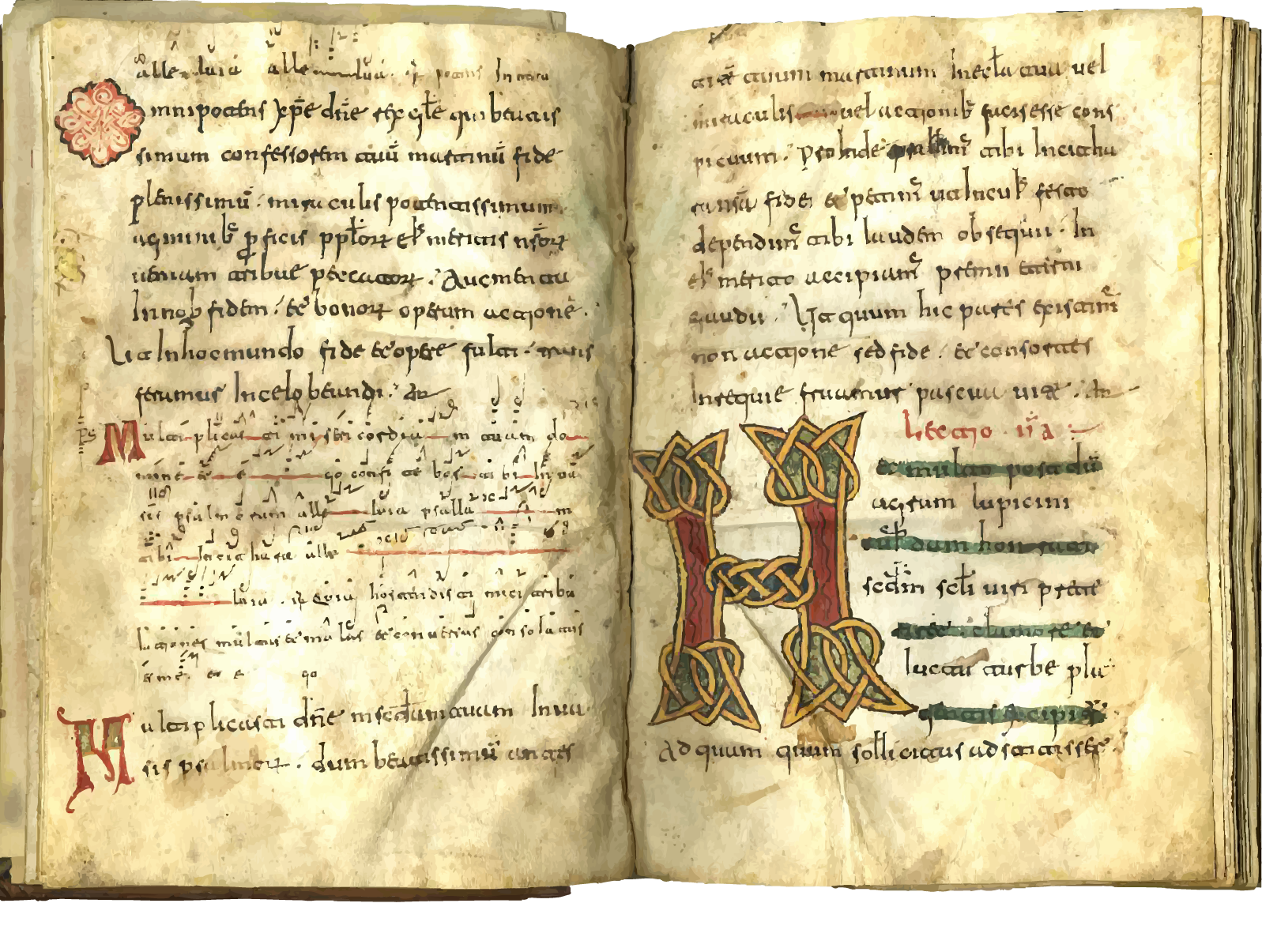

Liber misticus Santo Domingo de Silos, Biblioteca de la Abadía, MS 5. ff. XXv-XXr.

Hispanic chant, also known as Mozarabic chant, is a unique and ancient form of Christian liturgical music that developed in the Iberian Peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal) before the Roman Catholic Church adopted Gregorian chant as the standard.

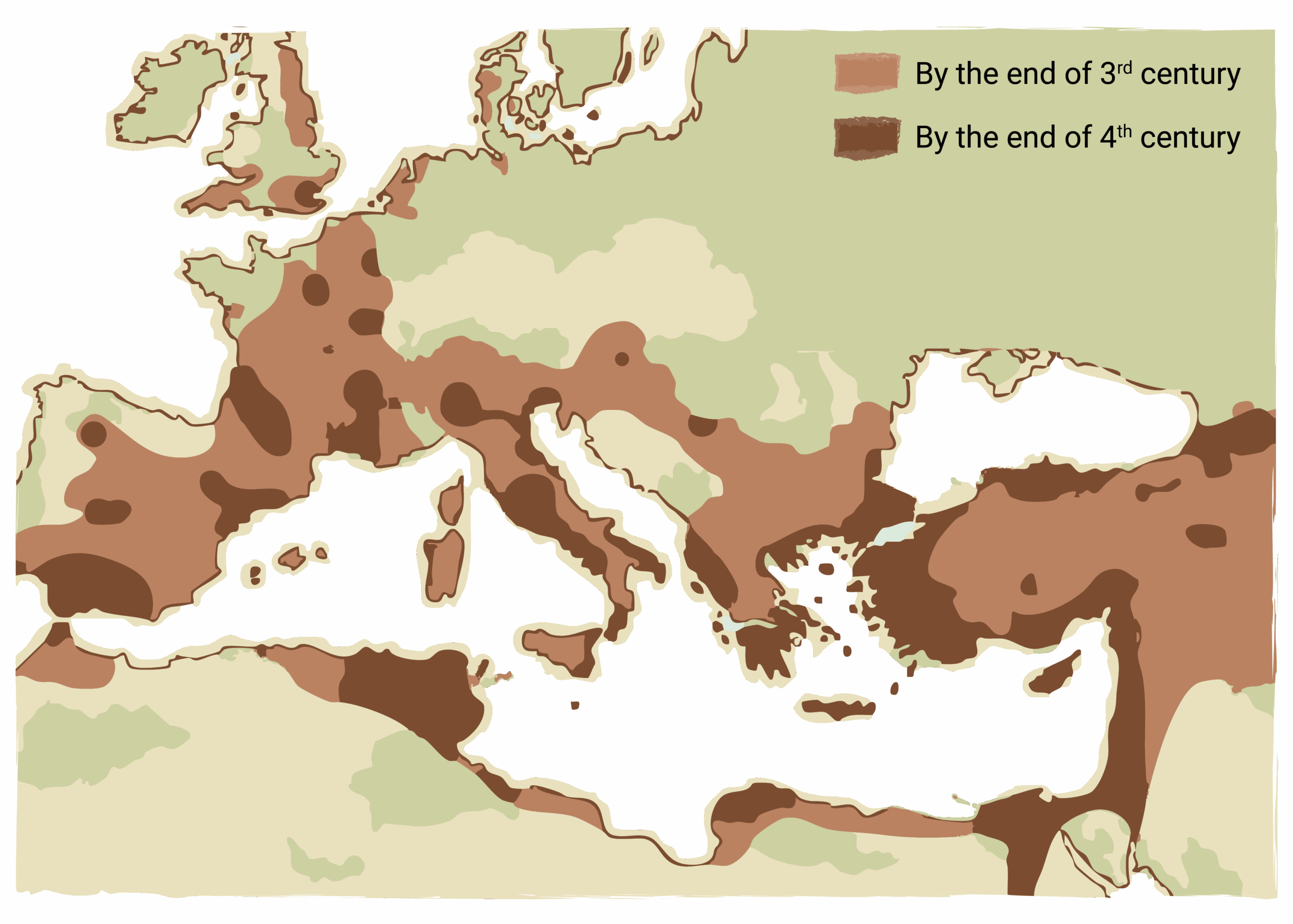

It was the official chant tradition of the Visigothic Church, which flourished in Spain from the 5th to the 8th centuries.

After the Arab conquest of great part of the Peninsula in the 8th century, this chant tradition was preserved and developed in both the northern Christian kingdoms of Iberia and in the Muslim south where Christians were allowed to continue observing the Hispanic rite and singing this repertoire.

Hispanic chant is characterized by its distinctive melodic and liturgical features, which set it apart from other Western chant traditions.

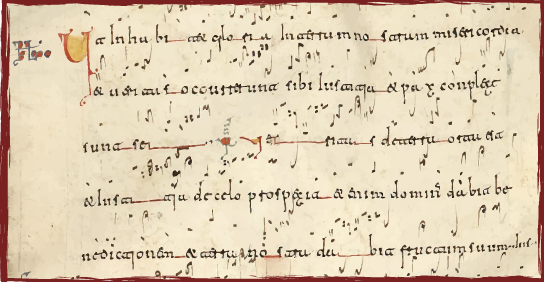

It often has a more ornate and melismatic musical style than Gregorian chant, with intricate vocal embellishments and several notes per syllable. The Hispanic chant’s musical notation is also noticeably complex and elaborate if compared with other plainchant notations.

In addition to chant genres shared with other plainchant traditions, such as responsories and antiphons, the Hispanic chant repertoire also includes genres that are unique to this tradition, such as the vespertini, soni, psallendi, and clamores, for example.

Liber misticus, E-Mah Cod. 30.

The origins of Hispanic chant can be traced back to the early centuries of Christianity, when various liturgical traditions developed in different regions of the Roman Empire.

Hispanic chant is a key element in the Hispanic rite, the distinct liturgical tradition that developed in Spain alongside the chant.

The Hispanic rite comprises many ancient elements of Christian worship, including unique prayers, readings, and rituals, alongside the chants.

In the 11th century, as part of the broader effort to unify liturgical practices across Western Europe, the Roman Catholic Church sought to replace the Hispanic rite with the Franco-Roman rite, which was and continues to be the Christian liturgy prescribed by Rome and followed in most of Western Europe.

The preservation of Hispanic chant is largely due to the continued use of the Hispanic rite in most Christian churches of the Iberian Peninsula until 1080, when the Council of Burgos decreed its abolition in favor of the Franco-Roman rite. Even after the adoption of the Roman Rite in most of the Peninsula, some Christian churches in the Muslim south, that is “Mozarabic churches”, continued to observe the Hispanic rite until it fell in disuse in the early 14th century. This musical repertoire has reached us in over 40 manuscripts (including fragments).

The earliest of these manuscripts, the Orational of Verona, is believed to have been produced in the early 8th century, in northern Iberia. Over 30 of these manuscripts, including the most complete Hispanic chant source, the Antiphoner of León, were copied in the 10th or 11th centuries, most likely in northern Iberia. Finally, around 10 Hispanic chant sources were copied after the official suppression of the Hispanic rite (year 1080) and before the 14th century and are associated with Toledo or other Mozarabic communities from the Muslim south.

Church of Santa Cristina de Lena (Asturias, Spain)

While Hispanic chant shares similarities with Gregorian chant in its use melodic patterns to indicate cadences, it does not follow the Gregorian modal system. The melody-types so far discovered in the Hispanic chant often feature unique melodic formulas, as well as idiosyncratic intonations and cadential patterns, further distinguishing this repertoire from other Western chant traditions and adding to its unique sound and appeal.

Hispanic chant holds a significant place in the Iberian cultural heritage, reflecting its rich and diverse history. It stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of the Visigothic church, offering a valuable window into the musical and liturgical practices of early medieval Spain.

One of the most striking features of Hispanic chant is its melismatic style, where long, flowing melodies are adorned with extensive vocal embellishments. These melodies often span a wide range and utilize intervals rarely heard in Gregorian chant, creating a distinctive and expressive quality. The use of microtones and ornamentation further enhances the unique character of the music.

Unlike the more structured rhythms of Gregorian chant, Hispanic chant exhibits a free and improvisational quality. Its rhythmic patterns are not strictly bound by meter or regular accents, showcasing a captivating blend of Eastern and Western musical influences. This rhythmic diversity contributes to the dynamic and engaging nature of Hispanic chant.

While Hispanic chant shares similarities with Gregorian chant in its use of a modal system, it retains a distinct character. The modes in Hispanic chant often feature unique melodic formulas and cadential patterns, further distinguishing it from other Western chant traditions and adding to its unique sound and appeal.

Beyond its historical significance, Hispanic chant has had a lasting impact on the development of Western music. Its distinctive musical, textual and theological features have inspired composers across various eras and genres, from sacred to secular. Even today, the study of Hispanic chant continues to inform and enrich our understanding of musical expression and creativity.

In recent decades, there has been a growing movement to revive and promote Hispanic chant. Scholars, musicians, and liturgical communities are dedicated to preserving and performing this ancient music, ensuring that it continues to resonate with audiences today and for generations to come. This revival reflects a broader trend towards rediscovering and celebrating the diverse tapestry of liturgical and musical traditions within the European heritage.